The past few years have been tough on Camila Pinto, who earned her PhD at the Federal University of Amazonas in Manaus, Brazil, in March. During her degree, she lost both her parents and had burnout and depression. Yet, her overall PhD experience was positive.

“We say in my lab that ‘life happens during a PhD’, and many personal dramas unfold,” says Pinto, a materials scientist who has now embarked on a postdoc and holds a salaried teaching position at Brazil’s Federal Institute of Amazonas in Presidente Figueiredo, a small town in the heart of the Amazon rainforest. “What helped me keep going was the personal support of my supervisor, the solidarity of our national scientific community and the belief that my research serves a greater good.”

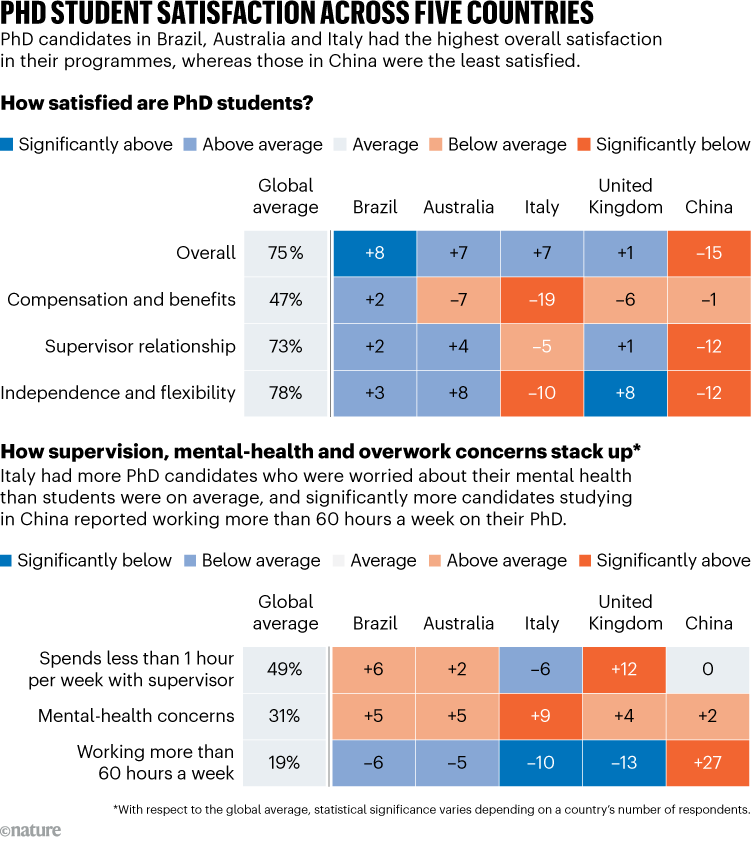

Pinto’s positive outlook might be a national characteristic. When Nature surveyed more than 3,700 doctoral candidates around the world earlier this year, Brazil stood out: 83% of respondents studying there reported being at least moderately satisfied with their PhD programme. It is the only country scoring significantly higher than the global average of 75%. Students in Brazil were also the most upbeat about their experience, with 80% saying that they enjoyed their degrees and 78% feeling fulfilled by their work, compared with global averages of 70% and 72%, respectively.

The only country that comes close to Brazil is Australia, which matches it on enjoyment and fulfilment, and scores just one point lower on satisfaction. Students in Australia and Brazil are also the most likely to say that their PhD experience matched their expectations, with 68% in Australia agreeing with this statement (including 29% who strongly agree) and 65% in Brazil (27% strongly agree).

Does that mean that these nations have the happiest PhD students in the world? In reality, the picture is more complex than that.

Before interrogating the survey data further, it’s important to set out some caveats. The self-selecting character of Nature’s PhD survey means that some countries are represented better than others. We received very few responses from some of the 107 nations. Eight had more than 100 participants, which makes comparisons between them robust: Australia (101 respondents), Brazil (113), China (312), Germany (247), India (430), Italy (111), the United Kingdom (201) and the United States (568). Another ten had between 50 and 100 respondents (Canada, Ethiopia, France, Iran, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Poland, South Africa, Spain and Switzerland) and were also included in this analysis. The remaining nations had too few participants to study individually (see ‘Nordic niceness’). Caution is therefore needed when comparing country-level results, says Elsie Lauchlan, quantitative director of London-based research consultancy Thinks Insight & Strategy, which ran the survey with Nature. And further complications arise from the fact that people based in various countries or regions tend to answer questions about satisfaction and well-being differently — an effect known as cultural response bias.

However, Izadora Menezes, who studies engineering at Brazil’s Federal University of São Carlos, disagrees with the idea that the nation’s PhD students are the happiest in the world. “Although I am satisfied with my personal experience with my PhD, I don’t think it reflects the reality in Brazil,” she says. Money is a key issue, she notes. Under then president Jair Bolsonaro’s far-right government from 2019 to 2023, scholarships stagnated and funding for science was slashed. Although Menezes’s scholarship from the São Paulo Research Foundation FAPESP is relatively generous, PhD stipends in the country can be as low as 3,100 reais a month, she notes. Although that is equivalent to a monthly allowance of US$1,250 in the United States, it is “usually insufficient for a comfortable life”, says Menezes. (Stipend values have been adjusted throughout to US dollars using a measure of purchasing power parity.)

Pinto thinks that the country’s high satisfaction rate might stem at least in part from relief that Bolsonaro’s presidency, which she calls a “dark chapter” for research, is over. “We are still struggling to rebuild much of what was lost, but for the first time in a long while, there’s a renewed sense of optimism,” she says. “That hopefulness is part of our DNA.”

Southern satisfaction

Like Brazil, Australia’s high satisfaction score is not immediately explained by Nature’s data. The country’s 101 respondents rate their satisfaction above average on most measures — for example, 58% of Australia-based PhD students feel satisfied with their work–life balance compared with 51% globally. But only the questions about tailored mental-health support and travel opportunities scored significantly higher than the global average.

Lifestyle factors, including outdoor culture and relatively safe living conditions, also add to improved well-being, says Eddie Attenborough, who studies food, bioprocesses and polymer science at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia. “When you’re happier outside of the lab, you’re more likely to feel fulfilled inside it,” he adds. Jesse Gardner-Russell, an ophthalmology PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne and national president of the Council of Australian Postgraduate Associations (CAPA), thinks that the country’s social safety nets are important, including free or subsidized health care for most PhD students, a diverse university culture in which international students feel welcome and a good work–life balance. “I think that all of this fits together to create satisfaction.”

The high proportion of international PhD students in Australia’s sample (63%) could also influence its satisfaction score. Globally, students doing a PhD abroad report significantly higher satisfaction than do those studying at home (78% compared with 74%).

Life in Australia is, however, expensive. Although the proportion of students reporting financial concerns (47%) is only slightly above the global average (42%), cost of living is consistently the top worry in CAPA’s surveys, Gardner-Russell says. A typical PhD stipend of Aus$33,500 a year (US$24,300) is below Australia’s minimum wage of around Aus$49,000. Moreover, unlike salaried jobs, stipends do not contribute to a pension plan, placing doctoral students at a disadvantage compared with their non-academic peers, he explains. “This can make PhD students feel very undervalued.”

Whereas Australia and Brazil scored high across the board, Italy offers a more nuanced picture. Overall, the country scores on a par with Australia: 82% of its 111 respondents say that they are at least moderately satisfied with their PhDs. But when asked whether they enjoy their degrees and feel fulfilled by the work, students in Italy score significantly lower than in the other two nations, with only 68% agreeing on both measures. They are also significantly less satisfied than average about pay, independence and work–life balance and have more concerns about their mental health.

Maria Roberta Belardo, who studies mathematical and physical sciences at the Scuola Superiore Meridionale in Naples, Italy, says that the country’s results reflect its complex academic landscape. Italian universities provide quality education, she says, but the pay is low — the average monthly stipend is €1,200 (US$1,960) after deductions — and the research community is small by European standards. Belardo says that many of the country’s PhD students are sustained mainly by their passion for their research topic. “In other words, Italian PhDs may feel proud of the degree they earn, while at the same time finding the experience itself less enjoyable and the professional outlook less secure, which, in my opinion, explains the mixed results of the survey.”

ADI, the Association of PhD Students and Postdocs in Italy, says that its 2024 survey, which received responses from some 7,000 PhD students in 2023, found that about half were at high risk of anxiety, depression and stress, caused mainly by economic insecurity, excessive workloads and uncertainty about the future. “In our opinion, if Italian PhD students declare themselves satisfied [in Nature’s survey], this satisfaction cannot be interpreted as an indication of idyllic living and working conditions. It could instead reflect a kind of ‘resilience’ or perhaps the prevalence of a ‘passion’ for research, which masks the daily difficulties,” says the ADI’s national secretary Davide Clementi, who is based in Palermo, Italy.

Dismal doctoral studies

If Italy’s students sent mixed messages in Nature’s survey, a stronger response comes from China, which had the lowest satisfaction score (60%) of the well-represented countries. Its 312 respondents are significantly less satisfied than average for many other metrics, too, including their supervisor relationships, research guidance, travel opportunities and independence. The nation reports the lowest proportions of students who enjoy their PhDs (53%) and feel fulfilled (63%). PhD salaries are also low compared with other nations: a government scholarship is worth around ¥42,000 a year (US$11,900).

Yanbo Wang, a science-policy researcher at the University of Hong Kong, says that much of the low satisfaction can be traced back to the long hours that China’s PhD students work — “at least 80 hours per week”, exceeding even the ‘996’ work schedule seen in some places, which involves working from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. This pressure to overwork stems from the high competition in the job market, Wang says. He estimates that the number of PhD students in China has at least doubled over the past decade, but the number of academic positions has not kept pace. And because PhDs are increasingly required for high-ranking jobs in government and state-owned enterprises, students face intense stress. “Life definitely is not easy,” Wang says.

But there might be more to China’s low satisfaction score — and, for that matter, Brazil’s high one — than just the students’ experiences. Other global surveys, including the World Happiness Report, an annual ranking of well-being, have found that self-reported satisfaction follows social, geographical and cultural norms. For instance, Latin American countries such as Brazil consistently report higher levels of subjective well-being than do other nations with similar or better economic circumstances (P. Beytía in Handbook of Happiness Research in Latin America; 2016). By contrast, life satisfaction in China declined during the country’s economic expansion from 1990 to 2005. Although China’s rank in the World Happiness Report has improved since 2010, it still ranks only 68th, despite being the world’s second-largest economy.

Traces of these patterns appear in Nature’s findings: PhD students in Brazil are much more likely than average to say that they are ‘extremely satisfied’ (17% compared with 8% globally) and to ‘strongly agree’ that they are enjoying their PhD overall (42% compared with 30%). Meanwhile, students in China are more likely to ‘strongly disagree’ (10%) than the global average (7%) that they are enjoying their PhDs. The United Kingdom had an average overall satisfaction score, despite its high individual scores for independence, intellectual challenge, work–life balance and good travel opportunities. And students there also receive a relatively high pay, with a yearly PhD stipend of at least £20,780 (US$30,600). The United Kingdom’s middling overall score could be interpreted as a quintessential example of British understatement.

Marie Briguglio, a behavioural economist at the University of Malta in Msida, explains psychology’s role in well-being surveys: even when asked the same set of questions, respondents have different approaches to their answers. “Some may compare their feelings to what they think others feel before answering. Some may compare their situation to their expectations. Others may be thinking of how they currently feel, while others may consider their feelings throughout” their PhD studies.

Culture also shapes responses, she explains. “In some cultures, lower ratings may be more common, as complaining is normatively accepted. In others, students may overstate their positive feelings to avoid being critical.” Even numerical rating scales can skew results. “Some people approach questionnaires with an implicit rule to avoid extremes, others simplify the process by answering only the extremes,” Briguglio says. “My seven may be equivalent to your five.”

Therefore, although there are demonstrably many satisfied PhD candidates in Brazil and Australia, this might not mean that students in these countries are better off than elsewhere. Nature’s data might suggest a slightly higher level of contentment in those nations, but whether that’s a result of external factors or internal attitudes is difficult to say.

What the data show, however, is that contentment can thrive even in adversity, to which Pinto can attest. She values her teammates deeply, “especially as we are one another’s main support network”, because she and her colleagues live far from Brazil’s academic centres. This year, her research group secured funding to expand its work on using rare-earth ceramics in energy-transition technologies. “This will help us overcome some of the limitations imposed by our geographic isolation and allow us to expand our infrastructure and collaborations,” Pinto says.

Nature’s survey can’t definitively tell us which country produces the happiest PhD students. But Pinto’s experience highlights what matters most: human connections, meaningful work and mentorship. In the end, these are the conditions that can make the PhD years rewarding no matter where you are based.

Find the original post and more great content on the Nature Careers website – Nature 646, 1013-1016 (2025) – doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-03346-4