There are some days when all I feel I do is write. We imagine the life of a scientist is spent in the lab running experiments and making discoveries. The reality is far different. The further along I progress in my career, the more time I spend outside the lab and in the office. Writing. But what am I writing about and how do I know if I’m any good at it? In this blog I consider whether being good at writing is necessary to be a successful researcher and academic.

The first significant piece of writing I had to do was as an undergraduate student. We had numerous 1500/2000-word essays and reports to write, all of which were designed to develop a particular scientific style of writing. For example, we were never to write in first-person, told not use “flowery” language (I’m still not sure what this is), and shown how to cite and reference properly. The more papers I read, the better my writing became. However, I also developed a habit during this time, which is still with me now over 15 years later; I write everything in long-hand. Even what I’m writing now, my pen is touching the paper and my left hand is smudging the ink as I write. But surely I didn’t write my dissertation long-hand? I did. My PhD thesis? Indeed. My published papers? Absolutely. Why on Earth would anyone do this?

For me, writing long-hand didn’t start as a choice. As an undergraduate student I worked in a pharmacy as a dispenser, which didn’t leave me a great deal of time outside of my lectures and seminars to do my coursework. Luckily my manager allowed me to do my uni work on the counter if we had no customers and if I had completed all my tasks. Back then, I couldn’t afford a laptop, so I made all my notes in the library and brought my file and notepad to the pharmacy where I would write my essays by hand. I would then type them up next time I was in the library, which also served as a chance to edit and tidy up what I had written. I stopped working in the pharmacy just before I started my PhD, but the habit stuck.

As a researcher, it is necessary to have a variety of different skills, from the highly technical lab skills to data analysis and presenting. The PhD is a good opportunity to develop these skills and most students will become reasonably competent at them all. Many will excel in some skill areas which opens up opportunities outside of academia, such as in industry, science communication, or data science. But for a career in academia, is one of these skills, writing in particular, more important than the others?

[1]

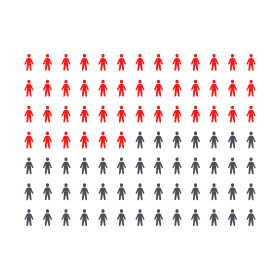

[1]The ISTAART UCL ECR Survey Found that 49.7% of ECRs thought they had too little time for writing and publishing research findings.

Let’s assume that everyone who completes their PhD is competent, if not good, at academic writing. Afterall, they have written a thesis. Beyond this stage, writing becomes an increasingly significant feature of a researcher’s workload. Firstly, there are manuscripts to write. We’re all familiar with the much-despised term “publish or perish”. Alongside this, researchers may want to find more accessible ways to communicate their science so they may write blogs for a platform like Dementia Researcher. Then there is the dreaded grant writing. Writing grants is something which takes up a significant amount of a researcher’s time, with only a 10-20% success rate which varies based on the funder. There is even a term reserved for this style of writing: “grantsmanship”. This basically means knowing how to write a good grant. It requires good scientific writing and structuring in way which neatly lays out the research area, the research questions which need addressing, and your plan for how you intend to answer these questions. It seems that if writing is not the most important skill to have to be successful in academia, it is certainly one which consumes a significant amount of time. Without being able to write grants, research cannot be funded, and without being able to write papers, it can be more challenging to disseminate and advance research once it is funded.

So what if you are not particularly strong at writing but you still want to pursue a career in academia? Firstly, it’s important to remember that writing is a skill which can be continually improved on. Even now, the more I read, the more I find my writing improving. I once went to a series of career development workshops and many of the postdocs discussed either lacking the time to write or struggling with motivation when they did have time. The advice we were given was to make writing a habit. To write something every day even if it’s nonsense and to try and create protected time for it. I feel like we often become paralysed with the thought of having to write a big piece of work like a manuscript or a grant, and then waste time trying to write the perfect first draft, when it all ends up heavily edited later anyway. But if we break it down into sections and accept that there will be editing later, then the pressure to write every sentence perfectly disappears.

When the edits do arrive in your inbox, it’s important not to be too disheartened when you see those dreaded track-changes from a colleague or supervisor making the work virtually unrecognisable. Over the years I have learnt that these edits are often down to personal style and nothing significant about the content usually changes. Sometimes it does, especially if I’m less experienced writing a type of document which might require a certain structure, for example. Or the time I was a PhD student and received reviewers’ comments on my second manuscript and they questioned whether I knew what an Oxford comma was. I didn’t, but I certainly do now. Either way, my writing is undoubtedly improved by the process of editing and peer review.

Being a good writer might make it easier to be a successful academic, but I don’t think it’s necessary. As researchers, we don’t work in isolation, which means that if you’re not particularly strong at writing you just need to ensure you have protected time to write and then the freedom to just get something, anything, written down as a very first draft. Good colleagues and mentors should edit and proofread for you to help you develop your writing.

Now, having written this blog, I’m reminded of the several manuscripts I’ve got sitting in draft form. So, I had better get writing.

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali

Author

Dr Kamar Ameen-Ali [2] is a Lecturer in Biomedical Science at Teesside University & Affiliate Researcher at Glasgow University. In addition to teaching, Kamar is exploring how neuroinflammation following traumatic brain injury contributes to the progression of neurodegenerative diseases that lead to dementia. Having first pursued a career as an NHS Psychologist, Kamar went back to University in Durham to look at rodent behavioural tasks to completed her PhD, and then worked as a regional Programme Manager for NC3Rs.