There are currently over 46 million people living with dementia worldwide, which is expected to increase to 131 million by 2050 [1]. As of 2011, dementia is costing the United Kingdom economy more than £27 billion per a year, which is believed to starkly increase due to people living longer, and age being the main risk factor for dementia [2]. In 2012, The World Health Organisation and Alzheimer’s Disease International declared dementia as a ‘public health priority’[3].

However, to date there are no disease-modifying drugs available for treatment of dementia, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most prevalent form of dementia [4]. In recent months there has been clashing responses to the alleged successful clinical trial results from the EMERGE study on aducanumab, which promises to reduce cognitive decline in patients by removing amyloid plaques [5]. Despite the hype concerning the drug, the concern still remains that we may be starting treatments far too late along the course of the disease: where cognitive decline and neurodegeneration are irreversible.

This past week I had the honour of listening to world-class speakers and researchers at the ‘Prediction and Prevention in Neurodegenerative Disease’ symposium held by the Preventative Neurology Unit, the School of Medicine & Dentistry at Queen Mary University. This group has been funded by Bart’s Charity and strives to carry out groundbreaking novel research concerning the prevention and prediction of diseases affecting the nervous system, such as: Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis (MS), and dementia.

Throughout the day, the Derek Willoughby lecture theatre echoed urgent concerns in improving research approaches towards predicting and preventing sporadic forms of dementia, by:

- Efficiently identify those at risk of developing sporadic forms of dementia, using sensitive screening devices that are cross-cultural and affordable.

- Identify modifiable lifestyle risk factors across the life span (e.g. hearing loss at midlife, smoking at later life).

- Predict when symptoms will develop.

- Anticipate the progression of the disease with disease modifying drugs present.

- Enhance the current performance of secondary services (e.g. memory clinics).

Using Vision to Predict Dementia

Some of exciting findings presented at the symposium include the use of visual tests to predict dementia risk in those with Parkinson’s disease. It is estimated that 50% of PD patients go on to develop dementia within 10 years of diagnosis [6]. Dr Rimona Weil’s team based in UCL found that those at risk did worse in multiple tests measuring visual processing, and displayed a thinner retina layer in areas containing dopaminergic cells (ganglion cell layer and inner plexiform layer) [7]. Despite deficits in visual processing and structural changes in the retina, patients did not report visual impairments.

Modifiable Lifestyle Factors

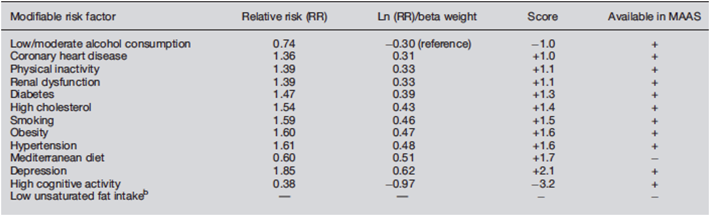

Dr Sebastian Köhler and his team from Maastricht University in the Netherlands, presented the ‘Lifestyle for Brain Health’ (LIBRA) score, which has been developed in order predict future risk of dementia as well as cognitive impairment [8]. A one-point increase in risk represents a 9% higher risk for cognitive impairment, and 19% risk for dementia. High LIBRA scores have also been associated with MRI based brain volumes.

‘Algorithm for calculating individual Lifestyle for Brain Health (LIBRA) score’ [8].

Virtual Reality (VR) Tests in Prodromal AD

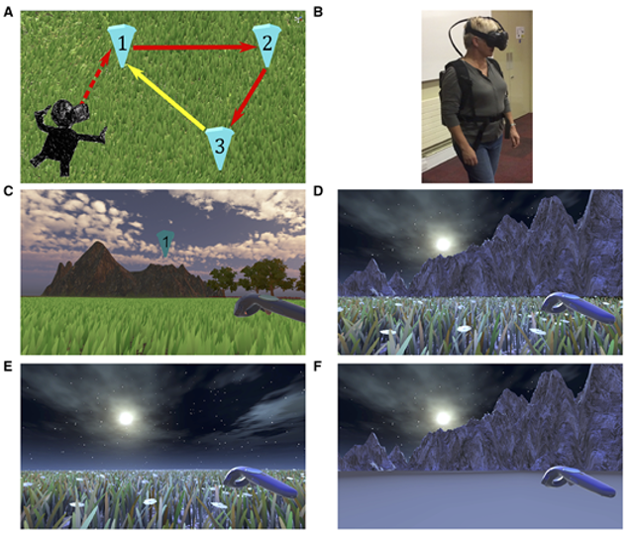

Dr Dennis Chan and his group at the University of Cambridge have focused on designing sensitive and affordable screening methods that detect the early progression of AD, by focusing on spatial neurons in the entorhinal-hippocampal circuit. The entorhinal cortex is the first region to exhibit neurodegeneration in AD, and is involved in spatial navigation, which is reflected by the firing of spatially modulated neurons [8]. The study findings highlighted that the biomarker positive patients presented larger errors in VR path integration tests, whereas biomarker negative patients and non-patients presented with similar navigation performance. VR performances correlated with MRI measures of the entorhinal cortex and AD molecular pathology, and was found to have higher diagnostic sensitivity and specificity than neuropsychological tests currently used in early detection and diagnosis of AD (e.g MMSE, ACE-R etc.)

‘Path integration task (A) Illustration of the path integration task. Each numbered inverted blue cone is a location marker. Only one cone was visible at a time; upon reaching a blue cone it disappeared and the next one in the sequence appeared. Red arrows indicate the guided sequence along two sides of the triangle. The yellow arrow, the last side of the triangle, signifies the assessed return path, performed in the absence of any cones. (B) Demonstration of VR equipment on a participant during the task, used with permission. (C) Example environment from the head mounted display with textural and boundary cues present, with cone 1 and the controller shown. Texture and boundary cues are present in all trials when navigating between cones. (D–F) Return conditions applied when attempting to return to the location of cone 1 only (yellow arrow, A) and included no change (D), removal of environment boundaries (E) and removal of surface detail (F)’[9].

Take Away Message

Dementia may be incurable at this current moment in time, but it is never too late to prioritise brain health and empower members of the public in being proactive in delaying the onset of cognitive decline.

Acknowledgement

Many thanks to Dr Charles Marshall and staff from the PNU group for organising this event, and the delightful speakers for sharing their groundbreaking research.

List of Speakers And Their Topics Of Discussion

- Anette Schrag (UCL): Detecting prodromal Parkinson’s disease.

- Rimona Well (UCL): Using vision to predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease.

- Seb Köhler (Maastricht University): Risk and prevention of dementia: the Dutch MijnBreincoach project.

- Vanessa Raymount (University of Oxford); Recent advances in the prevention of dementia, update from the European Prevention of Alzheimer’s Dementia study.

- Jonathan Schott (UCL): Exploring the prevalence, Causes and consequences of Alzheimer’s and cerebrovascular pathology in the 1946 birth cohort.

- Dennis Chan (University of Cambridge): VR tests of entorhinal cortex function in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease.

- Carol Brayne (University of Cambridge): Population studies of brain ageing in context.

- Richard Milne (University of Cambridge): Ethical challenges associated with the prediction and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.

- Alastair Noyce (QMUL): Time matters, A call to priorities brain health.

Phazha and a few others recorded a podcast for the Dementia Researcher website, to discuss the presentations at this symposium. Download now on your favourite podcast app, just search for Dementia Researcher – or stream directly from our website using the link below

Author

Phazha Bothongo is a PhD student at Queen Mary University of London and originally from South Africa. Her research interests focus on the effects of socio-economic deprivation and ethnicity on the prevalence of dementia in Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) groups, in comparison to the white population. In her spare time she can often be found at the Tate Modern, and in the cafe reading about spirituality and enlightenment.

References

- Mukadam, N., Lewis, G., Mueller, C., Werbeloff, N., Stewart, R. and Livingston, G. (2019) ‘Ethnic differences in cognition and age in people diagnosed with dementia: A study of electronic health records in two large mental healthcare providers’. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 34 (3), pp. 504-520. doi: 10.1002/gps.5046

- Moriarty, J., Sharif, N. and Robinson, J. (2011) ‘Black and minority ethnic people with dementia and their access to support and services’. Social Care Institute for Excellence. pp. 1-20. Available at:https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/a0ff/ 9a8105c4ef6f136ed62dc59875a6eaa36e64.pdf

- World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International (2012) ‘Dementia: a public health priority World Health Organization’.

- Mehta, D., Jackson, R., Paul, G., Shi, J. and Sabbagh, M. (2017) ‘Why do trails for Alzheimer’s disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective for 2010-2015’. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 26 (6), pp. 735-739. Doi: 10.1080/13543784.2017.1323868

- Alzforum (2019) ‘Therapeutics: Aducanumab). Available at: https://www.alzforum.org/therapeutics/aducanumab

- Lanskey, J. H., McColgan, P., Schrag, A. E., Acosta-Cabronero, J., Rees, G., Morris, H. R. and Weil, R. S. (2018) ‘Can neuroimaging predict dementia in Parkinson’s disease?’. Brain. 141 (9), pp. 2545-2560. Doi: 10.1093/brain/awy211

- Leyland, L.-A., Bremner, F. D., Mahmood., R., Hewitt, S., Durteste, M., Cartlidge, M. R. E., Lai, M. M.-M., Miller, L. E., Saygin, A. P., Keane, P. A., Schrag, A. E. and Weil, R. S. (2019) ‘visual tests predict dementia risk in Parkinson’s disease’. Neurology: Clinical Practice. (2019), pp. 1-11. Doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000719

- Schiepers, O. J. G., Köhler, S., Deckers, K., Irving, K., O’Donnel, C. A., van den Akker, M., Verhey, F. R. J., Vos, S. J. B., de Vugt, M. E. and van Boxtel, M. P. J. (2017) ‘Lifestyle for Brain Health (LIBRA): A new model for dementia prevention’. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2018 (33), pp. 167-175. Doi: 10.1002/gps.4700

- Howett, D., Castegnaro, A., Krzywicka, K., Hagman, J., Marchment, D., Henson, R., Rio, M., King, J. A., Burgess, N. and Chan, D. (2019) ‘Differentiation of mild cognitive impairment using an entorhinal cortex-based test of virtual reality navigation’. Brain. 142 (6), pp. 1751-1766. Doi: 10.1093/brain/awz116

Print This Post

Print This Post