This is going to be an advice column for those of you currently applying or considering applying for fellowships. Pre-warning, I’m having a bad day whilst writing this so it’s going to be grumpy.

There’s a springboard award which I was considering writing this week. If I was being really honest I should be writing it right now. I should be thinking of ideas and reading papers. Because, as it turns out from almost everyone I talk to, I write a pretty good grant. I know how to structure it, I know how to highlight my ideas. I managed to get fairly far through Wellcome and MRC with little to no input from senior scientists. I write well and I write quick but I’m not currently doing either. What I’m currently doing is doom-consuming pastry and staring at a blank Word document. Actually, it’s not blank. It contains the following crushing phrase:

End date of current contract (must be after the end date of the proposed 2-year springboard project)

What I should have done is apply for this as soon as I got my fellowship, at a point when we were peak pandemic and I had zero data. Now I can’t apply for it because I’m too far in and don’t have enough time left.

Okay so maybe let’s switch it up and not go fellowship, let’s try for project grant money. Open Je-S, try out a test MRC project grant. Oops, here we go again…

Post will outlast project: Select Yes (this is a compulsory grant condition).

Fail two of the day.

So…what to do. At the moment I don’t know. I’ve got some meetings coming up, but I’m torn. But you, you’re at the beginning of this journey so here are all my thoughts on how you should approach this because I’ve made these mistakes and I don’t want you to do the same.

The ISTAART ECR Survey published in April 2022 found that 76.1% of ECR respondents had under two years left on their contracts.

First, go into a big lab with lots of people and lots of money. I wish it didn’t work like this because these labs are often run by terrible people who are awful mentors. But at this point money begets money. They will not give you money unless you already have some so if you’re swimming in the stuff, it will be easier. A big lab with plenty of money will be a chance for you to sidle onto papers, making you look more successful and therefore more fundable.

Second, when you’re thinking about fellowship options you have two choices. Total independence with five years or some independence with three years. Here I will define some terms for you. There are totally independent three-year fellowships, I have one, I have a friend who had one. If you aim and plan to be totally independent with your three-year fellowship, you will suffer. Here’s why:

It is not possible for you to do practical lab work and analysis, keep up with the literature and carry out the role of a PI with all its inherent administrative tasks. I’m sorry to all you high achievers out there who think I’m moaning but it’s just not possible to do all of these things at the same time. It is possible to do two of these things, but not all of them. I can write grants and papers and do admin, but these take time out of my lab work. I can do lab work, but this takes time out of writing. And let’s not even consider adding teaching on top of that.

So, you can see how I got into the pickle up top, can’t you? I was so excited to have my own money I cracked on doing experiments and it was amazing. I loved it, and I still do. But I’m now screwed. Because I’m on my own and there’s only so much you can achieve solo, I don’t have enough data for papers (did I mention there was a pandemic?) and I also don’t have enough time left to write anything which might be funded now because I don’t have a long enough contract. End date of the proposal must be after the end date of the current contract, blah blah blah.

So, I have over 40 papers, some pretty good scientific ideas, I’ve had some pretty good students who’ve said some pretty nice things about my mentoring and supervision skills and I’m still pretty much ruined.

Did you know… in the UK, most Universities will look at add anything up to 40% as an overhead on grants. If the research is charity funded this can be capped but still claimed by the University via the Charity Research Support Fund.

And you, dear listener, need to bear this in mind when you’re applying. If you’re applying for three years, do it in a big lab with lots of support, preferably with a technician who can help you out so you’ve got a spare pair of hands. That way when you’re writing your first grant 8 months into your project, they can be cutting your brains or splitting your cells. Your mentor can co-share a PhD student with you and they can start looking for them before you get your fellowship because once you start it, you’ve already run out of time to get one because you need three or four years to officially supervise. If you’re not in a big lab then I’d suggest applying for five years, because it will allow you to start to be independent by giving you a post-doc as well as yourself. But the trouble is, if you’re not in a big lab the chances are you won’t have been ‘successful enough’ to get a five-year fellowship.

And here we actually run into one of the major problems with the funding and success of science, at least in the UK. Chris Liu from Oregon University writes some interesting research on this. You may remember him as the person who gave the optimum lab number as around 12, suggesting more is basically unmanageable and less is not productive enough, although all of this depends on the field. But as well as studying the ecology of labs he also studies genealogy, something which you also may not have thought of as part of your application process, but something which will almost certainly impact your career trajectory.

Ding and Liu started their 2021 paper title with the words coming from competitive stock. They looked at parent-progeny relationships in science where your parent is your PI and you are their progeny. They established that when the parent in this relationship is particularly successful, it’s better for the progeny to carve out their own niche. When the parent is what they describe as ‘low status’ it’s better for the progeny to toe the line. It’s an excellent overview of how relationships in science can influence the success or failure of those within the system and is definitely worth a read but, from my own interpretation (and I’m not a social scientist so don’t quote me here), what Liu and colleagues miss out of this is almost certainly a key factor.

Money.

They are measuring the status of the parent as prior to and after a big hit of cash and suggesting that the success or failure of progeny thereafter is to do with the inherent stature of their parent within the field. What they might be failing to spot is that it’s way easier to be successful if you have funds or time. If you have funds, you can employ more people to do more things in a shorter period of time. If you have time, i.e. a permanent contract, you can do plenty of stuff you just have to put up with the fact that you’ll do it over several years, rather than several months.

Taking their research findings in that context it’s easy to see how you can be successful by breaking away from a big successful lab. You’re surrounded by funds which you can lean on whilst you find your own way, you can share technical assistance and shiny equipment. If you’re in a smaller lab, or even a lab of one, the way you become successful is by collaboration. So there, the success of the progeny depends on collaborative efforts with the parent – toeing the line is how you look productive.

Someone compared starting a lab to starting a restaurant. Gruelling, back-breaking work which sometimes leads to failure. I initially thought it was a ridiculous idea but there are some parallels to the work here. It’s going to be easier to be a success if you start an upmarket sushi restaurant somewhere busy, like New York, than if you start it out in the sticks where your footfall is going to be significantly less. Lots of people train to be chefs and not all of them will run successful restaurants. For me, this is where the analogy fails. The training scheme for chefs sets you up to be a chef, not to be a restauranteur. The training scheme for scientists, as it stands, assumes you are going to be a PI. And there’s only so much space at the top. (still not sure I like this analogy, thoughts on a postcard please)

Now, here’s the clincher guys. If you have three years of funding, you’re going to have to really fight your way to the top. You’re going to have to squeeze all you can out of the time and money you have. So why are you hanging around here reading this? Go, do science.

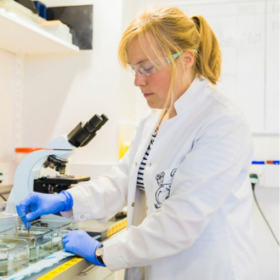

Dr Yvonne Couch

Author

Dr Yvonne Couch is an Alzheimer’s Research UK Fellow at the University of Oxford. Yvonne studies the role of extracellular vesicles and their role in changing the function of the vasculature after stroke, aiming to discover why the prevalence of dementia after stroke is three times higher than the average. It is her passion for problem solving and love of science that drives her, in advancing our knowledge of disease. Yvonne has joined the team of staff bloggers at Dementia Researcher, and will be writing about her work and life as she takes a new road into independent research.

Print This Post

Print This Post