If you ask any early career dementia researcher (in the UK but also elsewhere in the world) what they think about their work and career they will probably say… I’m passionate and love my job, however I constantly stress about the instability. Because my job depends on funding it is hard to put down roots (as I might need to move) and even if I wanted to, it’s hard to get a mortgage when you only have a 1-3 year contract. I also spend half of my current contract (or at least the last year) looking for my next. Finally, because I need to compete and ‘be the best’ to ensure I still have a job, I tend to say yes to everything and work long hours. I feel appreciated and unappreciated at the same time, and while I know where to get help and support, I don’t want to complain as this might have a negative effect on my career.

The road to becoming a fully-fledged academic can feel long, tough and filled with disillusion. A study by The Royal Society found that only 3.5% of students that complete a PhD secure a permanent research position at a university. Of those lucky few, only 12% (or 0.45% of the total) make it to professor level (this was in 2010, but it hasn’t improved).

Despite all of this, the vast majority of dementia research is actually done by people who we define as early career researchers, and despite their precarious situations, great progress continues to be made.

So is this pressure and competition a good thing or a bad thing? Bad, obviously.

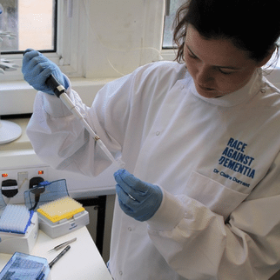

Race Against Dementia work with Alzheimer’s Research UK who support administration of their innovative Fellowship Programme.

We need research funders to fund people for longer, and to rethink the career structure to create more balance – 0.45% of PhD’s becoming Professors is crazy! A short-term fix might be to just fund more Fellowships, however talk to anyone at this stage (we have some podcasts coming on this topic) and they’ll tell you that all too often they end up in a perpetual loop of one short-term contract after another, until they eventually get lucky, leave or divert into a research ‘related’ position. There is also a reason why we have lots of PhD Students and fewer Fellows – they’re cheaper (okay that’s a simplistic view, and I agree it’s arguable – but it isn’t untrue). So the long-term fix has to be a rebalancing of the career, not only across career stages, but potentially where research happens. Early career dementia researchers aren’t unique, this problem faces most people who choose academic research careers. However, because dementia is so high-profile, could we use this to be trail-blazers and lead the way?

The good news is that this problem is being discussed more than ever, and research funders like Race Against Dementia (RAD) have started to disrupt the system. Their Fellowship Programme is now three years old, and as part of it, they fund people for 5 years (not three) and give these fellowships out to people at an earlier stage than is typical; not only that, but they also work with their fellows, treating them like elite athletes. In practice this means providing mentoring, performance coaching, connecting them to high-tech creative companies and even looking at things like their diet, exercise and connections to the wider community.

Of course other funders are doing things too, ISTAART has put a particular focus on supporting ECRs, and engaging with underrepresented groups, and people from low and middle-income countries. Of course here in the UK, we have Dementia Researcher (but I’m bias) and research groups are being amazing at self-starting support work, a great example of this is a recent collaboration between the Alzheimer’s Research UK networks at UCL and in Scotland to create a mentoring programme.

So there is some support out there, and if you’re lucky enough to get a RAD Fellowship, congratulations. In the meantime, what can you do about it?

Well research from Staffordshire University has found that a person can interpret a situation as either a ‘challenge’ or a ‘threat’. Those who react well under pressure are said to be in ‘the challenge state’ whereas those who don’t are in ‘the threat state’. The challenge state is associated with an increase in adrenaline, whereas the threat state is associated with an increase in the stress hormone, cortisol. Which state you are in has significant consequences, as they have been found to influence how much effort you put in, your concentration levels and finally, how well you perform under pressure.

This area of psychology has, to date, mainly been applied to sport. But can this theory also be applied to academics? That’s something that RAD have also considered, when Dr Penny Moyle their development programme lead partnered with Hintsa Performance, a coaching company who support nearly all current Formula 1 drivers – you can watch a webinar the ISTAART PIA to Elevate Early Career Researchers had with Dr Penny Moyle from RAD and Hinsta, to see them explain how they work.

Today, myself and my great ISTAART colleague Dr Beth Shaaban are speaking at a World Dementia Council Dialogue Event to talk about ECR careers. We’ll talk about the challenges and say that we need a new approach, new solutions and more support, because we think your research will benefit. I’m looking forward to engaging with the community and hearing what the other presenters have to say. In the meantime, I can think of no better group of people who are able to rise to this challenge (and avoid thinking of this as a threat), than all of you who are working to defeat dementia.

Finally, Albert Einstein once said “If A equals success, then the formula is A = X + Y + Z. Where X is work. Y is play. Z is keep your mouth shut”. He was a smart man, but it probably time we changed that mindset.

Author

Adam Smith was born in the north, a long time ago. He wanted to write books, but ended up working in the NHS, and at the Department of Health. He is now Programme Director in the Office of the NIHR National Director for Dementia Research (which probably sounds more important than it is) at University College London. He has led a number of initiatives to improve dementia research (including this website, Join Dementia Research & ENRICH), as well as pursuing his own research interests. In his spare time, he grows vegetables, builds Lego & spends most of his time drinking too much coffee and squeezing technology into his house.

Share your own thoughts on what needs to change to improve research careers – Reply in the box below

Print This Post

Print This Post