PhD students today face more challenges than most professors ever did. The supervisor has mentoring responsibilities beyond academic performance, including the student’s well-being. But can does your mentoring have to only come from your supervisor or manager? And what if you have finished your PhD, where do you turn? And how can mentoring help, how do you find the right balance between supervision and mentoring, and how can that be applied to you and your career?

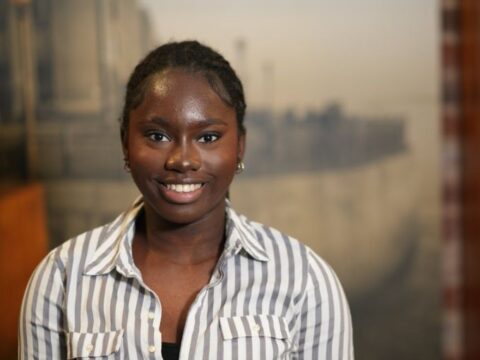

In this weeks podcast Megan O’Hare talks with Dr Ivan Koychev and Dr Christoph Mueller from the University of Oxford about the challenges, benefits and practicalities of mentoring.

Voice Over:

Welcome to the Dementia Researcher podcast, brought to you by DementiaResearcher.NIHR.AC.UK, a network for early career researchers.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Hello and welcome to our podcast recording for the NIHR Dementia Researcher website. This week we’ll be discussing mentoring. I’m joined today by Dr Ivan Koychev and Dr Christoph Mueller. Ivan is a clinical lecturer in old age psychiatry at the university of Oxford and a clinician scientist for Dementia Platforms UK. Christoph is an academic clinical lecturer at the department of old age psychiatry at Kings College, London. Welcome to you both and thank you very much for joining us today. Maybe let’s start with a brief introduction from you both about your research interests and how they led you to mentoring. First, Ivan.

Ivan Koychev:

Hi, thanks. Thanks for having me. Very briefly, what I work on at the moment is generally ways to improve the methodology, the way that we conduct trials. Experiments to find new treatments, especially for dementia. One of these things that I, one of the projects that I work on, it’s called the deep infrequent phenotyping study where we’re working to find biomarkers that can show who in the earliest stage of dementia are actually, who are the people who will progress to have a full blown condition and two, if we’re going to be testing new treatments in these people, what sort of biomarkers should we be looking at? How do we detect that something’s had an effect. The second part of my role is with Dementias Platform UK, which is again an MRC funded project that is bringing together data from over 40 cohorts around the UK.

Ivan Koychev:

My brief really is to develop a system where people are offered to do a brain health studies in dementia studies. It really is a very valuable population because these people who are already part of cohorts have a lot of data that’s been collected on them. We now know that we can only identify people who are in the prodrome or in the very early stages of dementia if we have a lot of data so that we can narrow down the individuals who are most likely to be 10 or 15 years before first symptoms. What I’m doing is developing the system to plug these people into clinical trials.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Okay. How has that led you into mentoring?

Ivan Koychev:

The story with the mentoring is that essentially since going into Oxford, I’ve been part of these multicentre studies and I got quite interested in the process of how do you set up such collaborations, what are the challenges? Really, I was looking for a mentor that would have this sort of overview and that’s how I came across professor Byrne from New Castle who’s similarly involved in quite a few collaborations of this sort. I thought would be an excellent person to get his ideas on, get his opinion on what I’m currently struggling with.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Great. Christoph, maybe a little background about your research interests.

Christoph Mueller:

Yeah. Again, my research is about complexity in dementia because kind of dementia is a very complex illness and people with dementia often have a lot of comorbidities. In fact, only kind of 5% of people with dementia just have dementia. Yet most kind of research and clinical trials is in all kinds of chronic illnesses. It’s just done preferably in people who only have that one illness. I’m kind of trying to look at how different interventions and different medications and classes of medication work in the complex syndrome that is dementia by looking at routinely collected data. By looking at electronic health records from recorded ETA mental health trusts, which is kind of locally their clinical record, interactive search system and yeah, basically assess how different interventions affect outcomes on the one hand. On the other hand, I’m quite interested in a subtype diagnosis of dementia. In particular kind of dementia with Lewy bodies because we know this is a type of dementia that has a much worse prognosis than other forms of dementia, but is yet very much under-recognized in clinical practice.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

How has your research led you into mentoring?

Christoph Mueller:

From the research point of view, I’ve kind of, I’ve gone [inaudible 00:04:36] the Academy of Medical Sciences who help clinical lecturers at this stage to identify an experienced mentor and you, you, you have a wide choice of mentors. I kind of, I decided I wanted to have someone outside my institution and even outside my field, the field of dementia research. I still have an epidemiologist, which is professor Peter Bernie who is an epidemiologist in respiratory care so that the mentor can give me a bit of a bird’s eye view on what I’m actually doing from a different field.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. That’s quite interesting. Do you find that with David Byrne as well, that he’s removed enough from your field that he can provide an outside influence or have you chosen him because he’s actually quite involved in your research field so he’s giving you pointers from inside? See what I mean?

Ivan Koychev:

SI guess the, the principle about mentorship is, as Christoph was saying, it’s always much more helpful if it’s somebody who’s very removed. They give you a sort of a completely unbiased view. I’ve gone sort of midway with David Byrne. He’s a neurologist who’s working on Parkinson’s disease. I found that it was a good midway solution because he’s done the very same things that I’m working on in Alzheimer’s, but he’s done them in a related field. I found that was going to be also a good thing to add to the mix.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Christoph, is your mentor in the same hospital as you, department?

Christoph Mueller:

No, but he’s based in London so it’s relatively easy for me to go and see him.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. Do you see him quite often then?

Christoph Mueller:

I mean, I would say I’m kind of doing it as needed. Initially, we kind of tried to say, okay, every month or every two months. I guess sometimes you adjust so you need to focus on something you need to get done. At this stage kind of can’t have that bird’s eye view or that overview. Then we have a longer break.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah, because you’ve sort of gone the other way and you’re based in Oxford even, but your mentor is based in Newcastle. That’s quite far away. Does that present any challenges or is that preferable to you?

Ivan Koychev:

It’s got its moments. So it’s a long journey on the train when I do go up. I think it’s nice because again, I think the thing about mentorship is that it gives you the option to sort of take a step back. I find it going through a long journey where you just on your own as well as a hundred other people in the train of course who are up to all sorts of things. It does make you, if you like free up two days, just to think about where are you going and then you meet the mentor, then they give you a bit of feedback, then you get another journey where again, you’re just thinking about this. Where if I compare it with a situation where the mentor was very close to where I was, I guess it’s something I could have done in an afternoon, which would have been a different dynamic.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. I guess it’s like a personalized conference just for you. You get the nice break away and they get to talk it all about you and your work.

Ivan Koychev:

There is definitely an element of talking about oneself for a change. Yeah.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. But your mentor, Christoph, although he’s in London so you don’t have the same commute aspect, it’s a different institution. I guess does that bring a different dynamic and an interesting dynamic because you’re seeing a different way of working as well, not just his ideas but also sort of how another centre works.

Christoph Mueller:

Yes. I think that kind of definitely helps. You kind of see how another centre has either the same problems, which is sometimes reassuring but also have find maybe creative solutions to things. I guess also the mentor has kind of this outside view and more the role of a sounding board and rather kind of facilitating your thinking. Of course, they will come in if they know the answer to a question, they will give you relatively concrete advice.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. This is all about sort of talking in the moment and using them as a sounding board like you said and articulating your ideas. Are they also helping with your future career and sort of guiding you? Do you find that as well, Ivan?

Ivan Koychev:

I think they do. I think they do. One of the things that I found particularly helpful with David is that he makes me think about the way that I’m going to present my, if you like, unique selling point in a year or two years’ time. Get me to think about this now, which is always a challenge. It’s always a challenge to think about these conceptual things and the way you would look like in somebody’s eye in a year or two years. I find it from that point of view it’s very good, but also, I find that the second thing is that it gives me the space to really think about the options and what am I going to do in two years in a way in which you just don’t get, maybe don’t get the time. Maybe you don’t get the space to think about this. From that point of view, I find that it’s really helpful.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. That was actually quite interesting because where people doing their PhD, I wonder whether this would actually be quite a nice, a mentoring scheme would be quite good for that because you’re not always thinking about the future. You’re mainly thinking about the thesis at the end of it. To have someone a bit further down the line saying, if you go to this conference and present this way, you will be seen like this. I don’t know. It’s a different way of thinking instead of just in the moment going, this is the most important thing that I’m doing. That’s interesting. I wanted to ask you whether either of you had been a mentor yourselves or whether you would consider it now?

Christoph Mueller:

Yeah. I’ve been kind of for a long time involved in what’s called the Maudsley mentoring scheme, where kind of junior psychiatrists are mentored by peers. It’s a peer mentoring scheme. Everyone who joins as a core training in psychiatry in their first year can apply to get a mentor who then will be a core trainee in their second year or higher. This scheme has been set up more than 10 years ago and has been kind of running successfully there. I have been also, it’s kind of, it’s different from academic mentoring in a lot of ways. I’ve kind of have been there to mentor core trainees or foundation doctors, whoever they have kind of at their very early stage, they have quite different needs than, than others.

Christoph Mueller:

However, what one has to say kind of if one is really trained up in mentoring and has had some training at least in a way everyone could mentor everyone by using the right techniques. Then it’s kind of finding a balance of kind of using your mentoring skills in situations where this might be more requiring you to have less knowledge or using your knowledge in situations where just know the answer to a question that the mentee has asked.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Okay. Ivan, would you consider being a mentor?

Ivan Koychev:

Absolutely. I think it’s great. I think we do bits of mentoring every day practice because in medicine there’s always about, the work is always about interaction with people from different disciplines and people who your, especially as you grow in seniority, you’re expected to provide some supervision, which I think a lot of the techniques that a good mentor does or a good mentor has to have a, the same ones applied to the principles of supervision. Yes, I would like to be a formal mentor. Just depending on whether there is anyone willing to subject themselves to it.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Christoph, you said that you have quite a purist view of mentoring and you said it’s quite paternalistic role. Could you expand on that a bit maybe?

Christoph Mueller:

Yeah. That’s basically kind of in a way, as I said, kind of the purist view of mentoring is everybody can mentor everyone as long as they have the correct training and the correct skills. Then I guess the polar opposite of this is having kind of this paternalistic role where the mentor kind of just does what they think is right. Kind of, I don’t know, pointing the mentee towards the right people or saying you have to apply for those grants and have to do, have to work with this one and have to be on this group and paper in a way. But I guess the best way as also Ivan alluded to is being somewhere in the middle and using kind of the right skills and techniques in the right moment for the right person.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. Okay. The Maudsley mentoring scheme, that’s just a for clinicians isn’t it?

Christoph Mueller:

I mean it’s largely kind of about clinical training. Of course, a lot of people can joining the Maudsley will have some academic interest and that’s often also a fear of mentors we are recruiting and training that if they don’t have that academic interest, that they still can be a good mentor. But if you kind of use certain techniques or use a certain mentoring model, that would certainly still be helpful for the mentee. Maybe in certain situations more helpful than someone who has actually the knowledge of the situation.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Okay, great. To go back a little bit to your research work, Ivan, one of the comments we’ve had back is people are really interested in finding out about how people are funded. This is quite off the mentoring thing, but you said that you’re MRC funded. Is that right?

Ivan Koychev:

The projects are MRC funded, but like Christoph, I presume at least, my main, my salary is NIHR. The academic clinical lectureship scheme is something that essentially is done as part of the training in psychiatry or training in medicine. It’s called integrated academic training where at the various stages of the training, it gives you the option to have just protected time for research as a high trainee. It’s called an academic clinical lectureship. Within this you get 50% of your time for research. Then this only covers your salary though, so if you want to work on projects, then these have to be funded separately. These two projects that I mentioned are funded by the medical research council. Another project that I work is called the prevent study, and it’s funded by the Alzheimer’s Society. There’s a variety of funding streams depending on what people are, the type of research that people do. But generally it’s either grant money for a project or it is a fellowship where it’s attached to you as it were.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. Have you found that your mentor has been able to help you with the application of grants?

Ivan Koychev:

The big application is once you’ve finished your training and you get to the so-called CCT, the completion of training, then the expected route is that you apply for one of the personal fellowships, which is in this case it’s clinician scientists fellowship. That is quite a high bar. What David has been brilliant in is in helping me shape what a potential fellowship would look like. Yeah, because he’s seen a lot of these.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

That is actually really useful because we’ve had people on here talking before about fellowships and how they can just look so daunting when you go to apply for them. But to have someone who’s kind of been there and done it in a way must be really useful. Is it similar for you, Christoph?

Christoph Mueller:

Yes, and I kind of can echo that certainly. It’s especially this early post-doctoral stage in a way where you get pulled in all kinds of directions. Kind of as a clinical lecturer, you kind of already, you see we are working on loads of different projects and it is kind of really difficult to really say which one is the main one and so forth. That’s what mentoring is kind of really helpful with. Is kind of really what is the big project that you’re going to do next as part of your, of a clinician scientist fellowship or similar. That’s kind of what I’m mainly talking about with my mentor.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Okay. Great.

Ivan Koychev:

Yeah. Narrowing down is usually, you’re right. Narrowing down is a problem because there’s so many interesting things that are happening in universities and things to get involved in. At some point, you just have to sort of focus on one thing and build it. It takes a while.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah.

Christoph Mueller:

The mentoring kind of really comes into finding that one thing that might make-

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Your unique selling point.

Christoph Mueller:

Yeah, or the unique selling point. That might be the next step.

Ivan Koychev:

Yeah. [crosstalk 00:18:30].

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. Okay. Have you got any other comments you’d like to make about mentoring? How has it helped your personal development, not just your career development?

Christoph Mueller:

I mean the, of course those mentoring skills, they are very helpful in any situation. I mean, they are even helpful in clinical situations. I mean, there is kind of all this whole idea of coaching for health that you kind of coach your patient to make the right lifestyle decisions instead of just saying you have to do them. They also have kind of to deal with all kinds of other challenging situations in a way.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Because you’re still very patient focused even though you’re 50% research, it’s still patient [inaudible 00:19:23].

Christoph Mueller:

Yes. Definitely and kind of patient focused teamwork, working in kind of complicated systems of hospitals.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Yeah. Okay. Ivan?

Ivan Koychev:

Yeah. No, I think it’s helped. Again, the main value I find is in the … A, in the fact that it provides the space for you to wonder about your own path and where you’re going and what the next stages would be. But also, we get so caught up in just everyday worries and every day … and especially in academia. There’s always, we’re a less stable type of profession then for a lot of other professions where you’re constantly expected to produce at a certain pace and there’s a number of different strands that you have to sort of pull on in order to make sure that you’re the complete package in the end. That of course is collected, is related to a lot of anxieties.

Ivan Koychev:

I find that it’s brilliant just to be able to sit down and to speak to somebody who’s done it already and to tell you that actually nobody really does it by the book and you’ll always find your way. All it takes is consistency and figuring out this sort of either unique selling point and just the way that you present a consistent message about new research. I find that that’s super helpful because otherwise if you don’t have that outside view, over time you just continue to build these worries and, “Oh. I’m not doing this right.”

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Oh, and second guess yourself a lot I guess.

Ivan Koychev:

Yeah. You just start assuming that the people who do manage to sort of get through are somehow superior in some unimaginable way. I think that’s really what mentorship does is that it brings you back to ground and so it has a professional, if you like, advantage, but also just on a very personal level, these are things that sort of impact you if you’re constantly worried about these things. I find that I always come away feeling a lot more relaxed and feeling like it’ll all be fine.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Okay. That’s nice. I feel like we all need a mentor in life. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Ivan Koychev:

Well, I’d like to thank my mentor David for the time that he’s spent and for his wise words. I find that it’s something that I’ve definitely benefited from and I can only recommend both mentorship in general and David also for any future mentees.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

How many mentees can he take on at once?

Ivan Koychev:

Well, let’s find out. Maybe he’ll need a mentor himself.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Well, we’ll give out his email at the end, but Christoph, would you like to thank your mentor?

Christoph Mueller:

Yes. Yes. Definitely. I mean, yeah. My mentor Peter Bernie, of course. Yes, and also, thank you for having us here to be able to share our experience.

Megan Calvert-O’Hare:

Well, thank you both very much. We hope you enjoyed this podcast. Please tweet Dem_researcher if you’d like to get involved or if you have any suggestions for further podcasts. Thank you.

Voice Over:

This was a podcast brought to you by Dementia Researcher. Everything you need in one place. Register today at DementiaResearcher.nihr.ac.uk

END

Like what you hear? Please review, like, and share our podcast – and don’t forget to subscribe to ensure you never miss an episode.

If you would like to share your own experiences or discuss your research in a blog or on a podcast, drop us a line to adam.smith@nihr.ac.uk or find us on twitter @dem_researcher

You can find our podcast on iTunes, SoundCloud and Spotify (and most podcast apps).

Print This Post

Print This Post